FEATURES

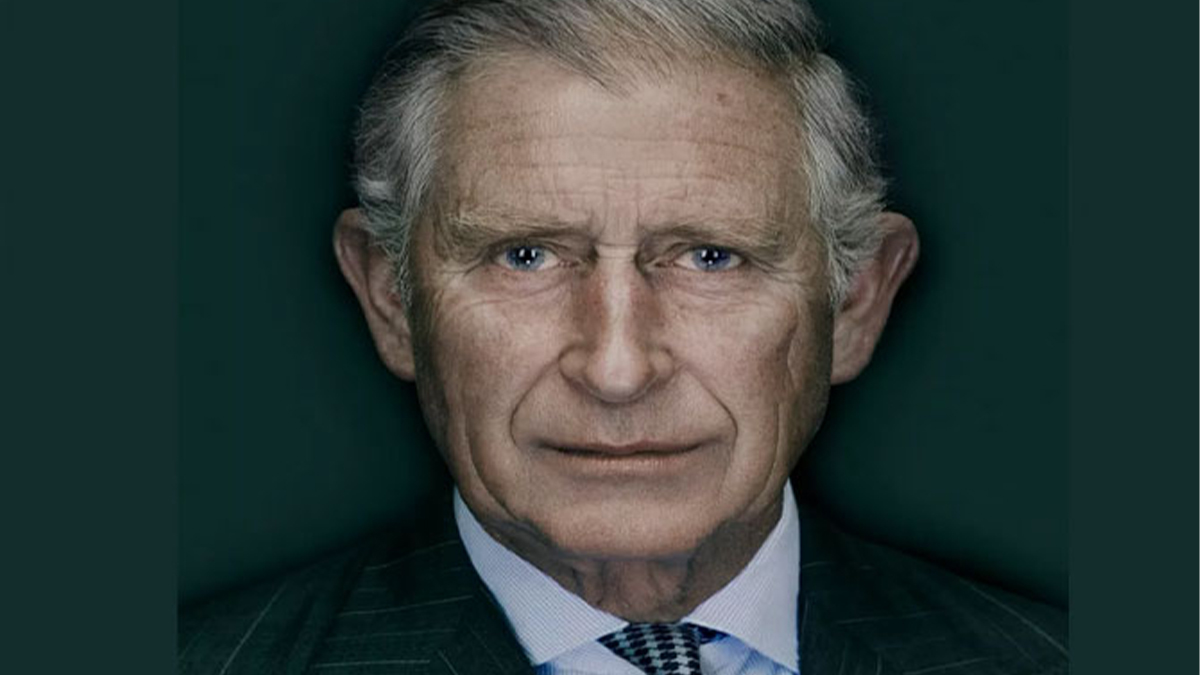

King Charles III, the new monarch

Published

3 years agoon

By

editor

At the moment the Queen died, the throne passed immediately and without ceremony to the heir, Charles, the former Prince of Wales.

But there are a number of practical – and traditional – steps which he must go through to be crowned King.

What will he be called?

He will be known as King Charles III.

That was the first decision of the new king’s reign. He could have chosen from any of his four names – Charles Philip Arthur George.

He is not the only one who faces a change of title.

Although he is heir to the throne, Prince William will not automatically become Prince of Wales – that will have to be conferred on him by his father. He has inherited his father’s title of Duke of Cornwall – William and Kate are now titled Duke and Duchess of Cornwall and Cambridge.

There is also a new title for Charles’ wife, Camilla, who becomes the Queen Consort – consort is the term used for the spouse of the monarch.

Formal ceremonies

It is expected that Charles will be officially proclaimed King on Saturday. This will happen at St James’s Palace in London, in front of a ceremonial body known as the Accession Council.

This is made up of members of the Privy Council – a group of senior MPs, past and present, and peers – as well as some senior civil servants, Commonwealth high commissioners, and the Lord Mayor of London.

More than 700 people are entitled in theory to attend, but given the short notice, the actual number is likely to be far fewer. At the last Accession Council in 1952, about 200 attended.

At the meeting, the death of Queen Elizabeth will be announced by the Lord President of the Privy Council (currently Penny Mordaunt MP), and a proclamation will be read aloud.

The wording of the proclamation can change, but it has traditionally been a series of prayers and pledges, commending the previous monarch and pledging support for the new one.

This proclamation is then signed by a number of senior figures including the prime minister, the Archbishop of Canterbury, and the Lord Chancellor.

As with all these ceremonies, there will be attention paid to what might have been altered, added or updated, as a sign of a new era.

The King’s first declaration

The King attends a second meeting of the Accession Council, along with the Privy Council. This is not a “swearing in” at the start of a British monarch’s reign, in the style of some other heads of state, such as the President of the US. Instead there is a declaration made by the new King and – in line with a tradition dating from the early 18th Century – he will make an oath to preserve the Church of Scotland.

After a fanfare of trumpeters, a public proclamation will be made declaring Charles as the new King. This will be made from a balcony above Friary Court in St James’s Palace, by an official known as the Garter King of Arms.

Queen Elizabeth II crowned her son Charles as Prince of Wales in 1969

He will call: “God save the King”, and for the first time since 1952, the national anthem will be played with the words “God Save the King”.

Gun salutes will be fired in Hyde Park, the Tower of London and from naval ships, and the proclamation announcing Charles as the King will be read in in Edinburgh, Cardiff and Belfast.

The coronation

The symbolic high point of the accession will be the coronation, when Charles is formally crowned. Because of the preparation needed, the coronation is not likely to happen very soon after Charles’s accession – Queen Elizabeth succeeded to the throne in February 1952, but was not crowned until June 1953.

For the past 900 years the coronation has been held in Westminster Abbey – William the Conqueror was the first monarch to be crowned there, and Charles will be the 40th.

It is an Anglican religious service, carried out by the Archbishop of Canterbury. At the climax of the ceremony, he will place St Edward’s Crown on Charles’s head – a solid gold crown, dating from 1661.

This is the centrepiece of the Crown Jewels at the Tower of London, and is only worn by the monarch at the moment of coronation itself (not least because it weighs a hefty 2.23kg – almost 5lbs).

Unlike royal weddings, the coronation is a state occasion – the government pays for it, and ultimately decides the guest list.

There will be music, readings and the ritual of anointing the new monarch, using oils of orange, roses, cinnamon, musk and ambergris.

The new King will take the coronation oath in front of the watching world. During this elaborate ceremony he will receive the orb and sceptre as symbols of his new role and the Archbishop of Canterbury will place the solid gold crown on his head.

Head of the Commonwealth

Charles has become head of the Commonwealth, an association of 56 independent countries and 2.4 billion people. For 14 of these countries, as well as the UK, the King is head of state.

These countries, known as the Commonwealth realms, are: Australia, Antigua and Barbuda, the Bahamas, Belize, Canada, Grenada, Jamaica, Papua New Guinea, St Christopher and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, New Zealand, Solomon Islands, Tuvalu.

(BBC News)

You may like

-

Passengers jump from plane’s wing after fire alert on Spain flight, triggers panic

-

CBSL extends Perpetual Treasuries suspension for six months

-

Kataragama Basnayake Nilame pressured over complaint against Kapuwas’ donation misuse

-

03 arrested over land grab at Bogahapelessa reserve

-

Big Beautiful Bill පනතට අමෙරිකානු ජනපති අත්සන් තබයි

-

Tense situation at Galle Face as illegal stalls removed

FEATURES

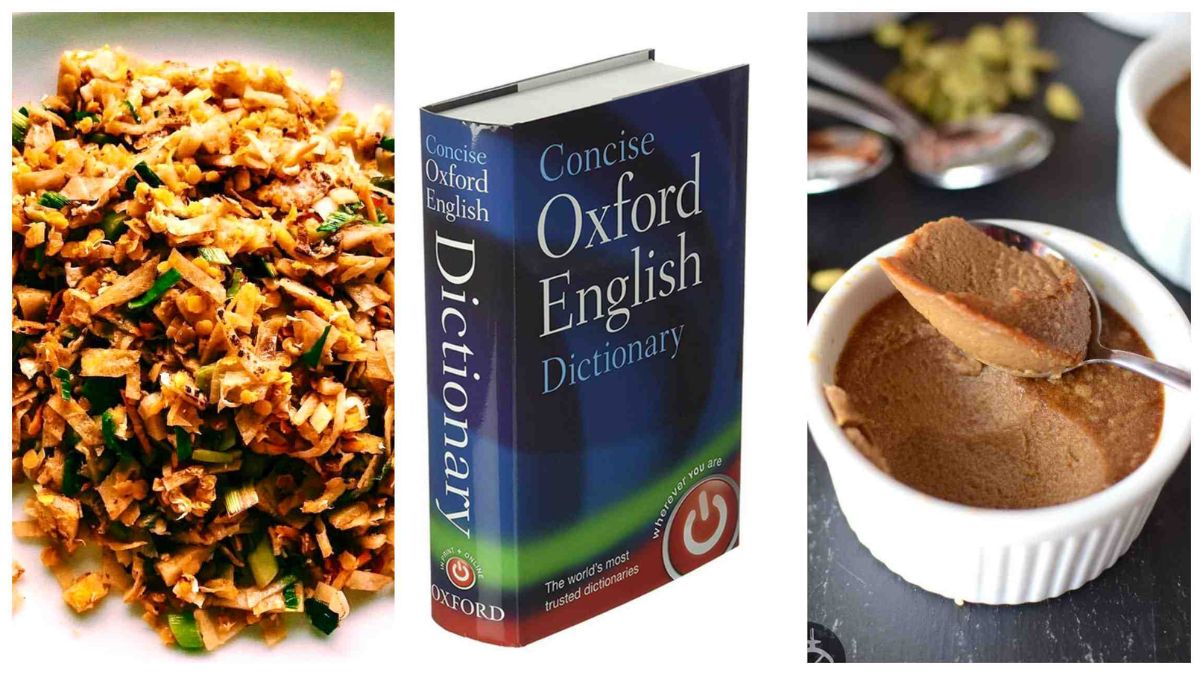

Asweddumized fields and sizzling kottu roti: New words from Sri Lanka

Published

1 week agoon

June 26, 2025By

editor

In a letter dated 7 October 1971 and sent from Panadura, Ceylon, OED contributor Pearl Cooray wrote to then Chief Editor Robert Burchfield: ‘I have looked up references for the word asweddumize and have succeeded to a certain extent. The Sinhala word aswedduma means “land recently converted into a paddy field”, and the Anglicized word asweddumize means to prepare a field for sowing paddy’. Cooray was a Sri Lankan academic who visited Burchfield in Oxford earlier in 1971, and upon returning to her country and her position in the Dictionary Department of the University of Ceylon, briefly corresponded with the OED, sending the above quoted letter as well as a selection of Sri Lankan newspapers and magazines for the reading programme for the OED Supplements that were in preparation at the time. Her suggestion for asweddumize would have been too late for the word to be considered for Volume I of the Supplements, so Burchfield wrote the word and definition on a paper slip, the main means by which words were tracked until the 2010s, and filed it alongside an earlier slip from July 1970 with the same suggestion from another Sri Lankan contributor, D. N. Ponnamperuma.

Nothing further is found about asweddumize in the OED’s files until 1986, when botanist D. J. Mabberley, a regular consultant for the Supplement, sent in a quotation slip for the word, which he would have encountered during the time he spent at a university in Sri Lanka. A decade later, another slip records the decision made not to draft an entry for asweddumize due to lack of evidence. ‘Omit (sadly)’was the responsible editor’s regretful note on the slip.

Almost thirty years later, this sad omission has finally been rectified, with the addition of asweddumize to the OED as part of this update. Current OED Sri Lankan English consultant Rochana Jayasinghe’s research on Pearl Cooray and her contributions to the Supplement helped put asweddumize back on the OED’s radar, and now that the dictionary’s editors have wider access to historical and contemporary Sri Lankan sources than their counterparts in the 1970s and 80s, it was possible to find sufficient evidence for the word, including a first quotation from as far back as 1857.

Joining asweddumize among this batch of new words are other borrowings from Sinhala, the Indo-Aryan language primarily spoken by the Sinhalese, the largest ethnic group in Sri Lanka. Mallung (first attested 1893) is lightly cooked, shredded (often leafy green) vegetables mixed with fresh grated coconut, chilli, and other spices, served as a side dish, salad, or condiment as part of a typical Sri Lankan meal, while kiribath (1886) is a Sri Lankan dish made with rice cooked in coconut milk and formed into a block, typically sliced into diamond-shaped pieces and served with various types of onion relish or sweetened with jaggery. Kiribath is traditionally eaten at special occasions such as Avurudu (1881), the first day of the Sinhala and Hindu New Year, occurring on the spring equinox (usually falling around 14 April), marked by a period of celebration typically lasting for seven to ten days.

Other Sri Lankan English words in this update originate both in Sinhala and another widely spoken language on the island, Tamil. Kottu roti (1991) is a Sri Lankan dish consisting of pieces of roti, meat, and vegetables, mixed with spices and curry sauce, and chopped by cleavers as they are cooked on a griddle. It is typically associated with the distinctive sound of the cleavers hitting the griddle as it is prepared by roadside vendors, and its name combines the Tamil word kottu ‘chopped’ with the Sinhala word roṭi ‘bread’. Partly a borrowing from Sinhala and partly a borrowing from Tamil, watalappam (1956) is a custard made from coconut milk (or sometimes condensed milk), cashew nuts, eggs, and spices such as cardamom and cloves, sweetened with jaggery and traditionally eaten by Sri Lankan Muslims during celebrations marking the end of Ramadan.

Sri Lankan music is represented by the words baila (1973) and papare (2006). Baila, a loan word from Portuguese, refers to an uptempo style of popular music originating in Sri Lanka which combines influences from both Africa and Europe, typically played in 6-8 time, with a syncopated rhythm, as well as to the style of dance performed to this music. Often associated with weddings and other celebrations, types of baila music are also popular in Goa and in the city of Mangaluru, on India’s west coast. Papare, on the other hand, is a genre of Sri Lankan music usually played at cricket and other sports matches, characterized by lively rhythms and typically featuring instrumentation of trumpet, saxophone, trombone, and snare and bass drums.

Apart from adding new Sri Lankan English words, OED editors have also revised a number of existing Sri Lankan English entries in the dictionary. Both these new and revised entries have been given transcriptions and audio pronunciations based on a new pronunciation model for Sri Lankan English, which is explained in more detail in this article. These enhancements to the OED’s coverage of Sri Lankan English help provide a more complete picture of how the language is used islandwide.

Full list of World English additions and revisions in the OED June 2025 update

(oed.com)

FEATURES

Dog-sized dinosaur that ran around feet of giants discovered

Published

2 weeks agoon

June 25, 2025By

editor

The full name of the new species is Enigmacursor mollyborthwickae dinosaur

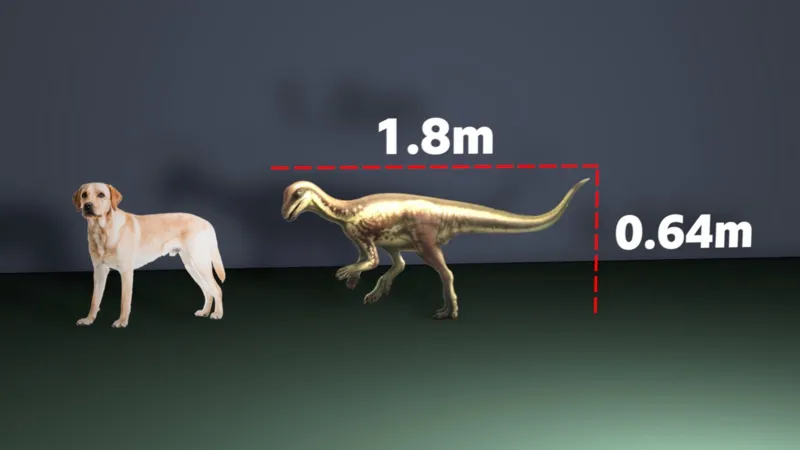

A labrador-sized dinosaur was wrongly categorised when it was found and is actually a new species, scientists have discovered.

Its new name is Enigmacursor – meaning puzzling runner – and it lived about 150 million years ago, running around the feet of famous giants like the Stegosaurus.

It was originally classified as a Nanosaurus but scientists now conclude it is a different animal.

On Thursday it will become the first new dinosaur to go on display at the Natural History Museum (NHM) in London since 2014.

BBC News went behind the scenes to see the dinosaur before it will be revealed to the public.

The discovery promises to shed light on the evolutionary history that saw early small dinosaurs become very large and “bizarre” animals, according to Professor Paul Barrett, a palaeontologist at the museum.

When we visit, the designer of a special glass display case for the Enigmacursor is making last-minute checks.

The dinosaur’s new home is a balcony in the museum’s impressive Earth Hall. Below it is Steph the Stegosaurus who also lived in the Morrison Formation in the Western United States.

Enigmacursor is tiny by comparison. At 64 cm tall and 180 cm long it is about the height of a labrador, but with much bigger feet and a tail that was “probably longer than the rest of the dinosaur,” says Professor Susanna Maidment.

The Enigmacursor was a small dinosaur that lived alongside some of the biggest known

“It also had a relatively small head, so it was probably not the brightest,” she adds, adding that it was probably a teenager when it died.

With the fossilised remains of its bones in their hands, conservators Lu Allington-Jones and Kieran Miles expertly assemble the skeleton on to a metal frame.

“I don’t want to damage it at this stage before its revealed to everybody,” says Ms Allington-Jones, head of conservation.

Conservators Lu Allington-Jones and Kieran Miles assembled the dinosaur onto a frame for display

“Here you can see the solid dense hips showing you it was a fast-running dinosaur. But the front arms are much smaller and off the ground – perhaps it used them to shovel plants in its mouth with hands,” says Mr Miles.

It was clues in the bones that led scientists at NHM to conclude the creature was a new species.

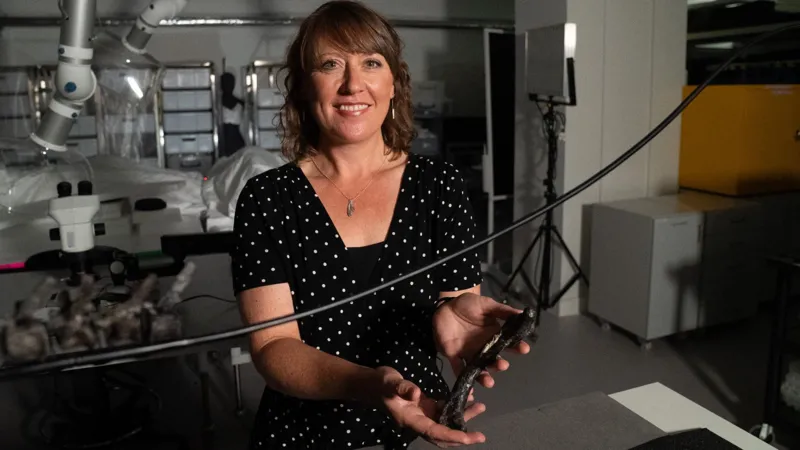

“When we’re trying to identify if something is a new species, we’re looking for small differences with all of the other closely-related dinosaurs. The leg bones are really important in this one,” says Prof Maidment, holding the right hind limb of the Enigmacursor.

When the dinosaur was donated to the museum it was named Nanosaurus, like many other small dinosaurs named since the 1870s.

But the scientists suspected that categorisation was false.

To find out more, they travelled to the United States with scans of the skeleton and detailed photographs to see the original Nanosaurus that is considered the archtype specimen.

“But it didn’t have any bones. It’s just a rock with some impressions of bone in it. It could be any number of dinosaurs,” Professor Maidment said.

Susanna Maidment travelled to the US to look at the original Nanosaurus dinosaur

In contrast, the NHM’s specimen was a sophisticated and near-to-complete skeleton with unique features including its leg bones.

Untangling this mystery around the names and categorisation is essential, the palaeontologists say.

“It’s absolutely foundational to our work to understand how many species we actually have. If we’ve got that wrong, everything else falls apart,” says Prof Maidment.

The scientists have now formally erased the whole category of Nanosaurus.

They believe that other small dinosaur specimens from this period are probably also distinct species.

The discovery should help the scientists understand the diversity of dinosaurs in the Late Jurassic period.

Smaller dinosaurs are “very close to the origins of the large groups of dinosaurs that become much more prominent later on,” says Prof Barrett.

“Specimens like this help fill in some of those gaps in our knowledge, showing us how those changes occur gradually over time,” he adds.

Looking at these early creatures helps them identify “the pressures that finally led to the evolution of their more bizarre, gigantic descendants,” says Prof Barrett.

The fossilised remains are the most complete of any in the world for early small dinosaurs

The scientists are excited to have such a rare complete skeleton of a small dinosaur.

Traditionally, big dinosaur bones have been the biggest prize, so there has been less interest in digging out smaller fossils.

“When you’re looking for those very big dinosaurs, sometimes it’s easy to overlook the smaller ones living alongside them. But now I hope people will keep their eyes close to the ground looking for these little ones,” says Prof Barrett.

The findings about Enigmacursor mollyborthwickae are published in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

– Georgina Rannard

Science correspondent

(BBC News)

FEATURES

JVP-NPP should learn difference between “marine research” & “surveillance”

Published

2 weeks agoon

June 21, 2025By

editor

There’s now an apparent stand-off between the UN FAO and the Foreign Affairs Minister Vijitha Herath on the request made by the FAO to have permission for the UN flagged “Dr. Fridtjof Nansen” marine research vessel to enter Sri Lankan waters. Minister Herath is on record saying the request would have to wait till the Committee on Standard Operating Procedures (SOP) for foreign research vessels appointed by him and perhaps chaired by him too, complete their task in formulating the SOP. It was revealed, the SOP Committee is yet to be convened for the first time. With “Dr. Fridtjof Nansen” marine research vessel waiting in Mauritius to set sail to Sri Lanka, numerous discussions the UN had with the Foreign Ministry (FM) since April has only reached the point, where the SL FM agreed to allow the ship to pick Bangladeshi “Scientists” from Colombo, but not get involved in any research in our waters.

res (SOP) for foreign research vessels appointed by him and perhaps chaired by him too, complete their task in formulating the SOP. It was revealed, the SOP Committee is yet to be convened for the first time. With “Dr. Fridtjof Nansen” marine research vessel waiting in Mauritius to set sail to Sri Lanka, numerous discussions the UN had with the Foreign Ministry (FM) since April has only reached the point, where the SL FM agreed to allow the ship to pick Bangladeshi “Scientists” from Colombo, but not get involved in any research in our waters.

What’s this whole calamity over a FAO marine research ship requesting permission to enter Sri Lankan waters? Someone somewhere at the helm of the Foreign Ministry, or the Foreign Minister himself has wholly misinterpreted the issue of country owned research ships visiting Sri Lanka and the moratorium that was imposed by President Wickramasinghe barring foreign research ships.

Sri Lanka was pressured by India and the US to curtail if not stop Chinese research ships from docking in our ports in the past few years. Special concerns were over the 02 research ships “Yuan Wang 5” that docked at Hambantota in early 2022 during Gotabhaya’s presidency and “Shi Yan 6” in October 2023 at the Colombo port during Wickramasinghe’s presidency. It was said, these 02 research ships had the capacity for surveillance and monitoring the region. Under pressure especially from New Delhi, President Wickramasinghe decided to impose a one year moratorium on foreign research ships visiting Sri Lanka, effective from early January 2024.

The Wickramasinghe moratorium came to its end on 05 January 2025, as the JVP-NPP government did not extend it further. Reason to allow the moratorium to lapse in January, may have been on a strictly confidential agreement reached to have a separate bi-lateral agreement on defence, during President Anura Kumara’s maiden official visit to India in mid-December 2024. Defence had been an issue discussed with Indian authorities during President Anura Kumara’s Indian visit, wrote Dr. Samatha Mallempati of “Indian Council of World Affairs” in May 2025. A defence MoU would thus make the moratorium irrelevant thereafter. PM Modi was to visit Sri Lanka 04 months later in early April this year. One among the many MoUs the 02 governments signed during PM Modi’s visit was the first ever Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) on “defence co-operation”.

India began working on a defence strategy for Indian Ocean Region (IOR) since the conclusion of Sri Lanka’s North-East civil war in 2009. New Delhi was very much concerned over President Rajapaksa’s post-war association with not only China, but with Pakistan too. Both with long time hostile border disputes with India. Contributing an article to “Stimson.org” on Pakistan-Sri Lanka relations in March 2021, two researchers on South & East Asian geo-politics Riaz Khokhar and Asma Khalid wrote, “In 2016, Pakistan signed a defense agreement with Sri Lanka to provide Colombo with eight JF-17 fighter aircrafts. Pakistani and Sri Lankan armies and naval forces have also regularly interacted through port calls, military and naval training and exercises, and defense workshops and seminars. In the recent high-level visit to Colombo, the Pakistani premier offered a USD $50 million credit line to Sri Lanka to further enhance defense and security partnerships.”

South Asian geo-politics did have new developments with post-war Sri Lanka compromising its economic needs with defence and national security in challenging the Tamil Diaspora canvassed US-Euro resolutions at UNHRC Sessions. Rajapaksa government was required to accept independent international investigations on war crimes and crimes against humanity, with many top military officers named. Pakistan stood with Sri Lanka, voting against all such resolutions at every UNHRC Session, while the Rajapaksa regime joined the Belt and Road Initiative of China, and was financially supported by China. Financial support that led to the popular adage “Sri Lankan type Chinese debt trap”.

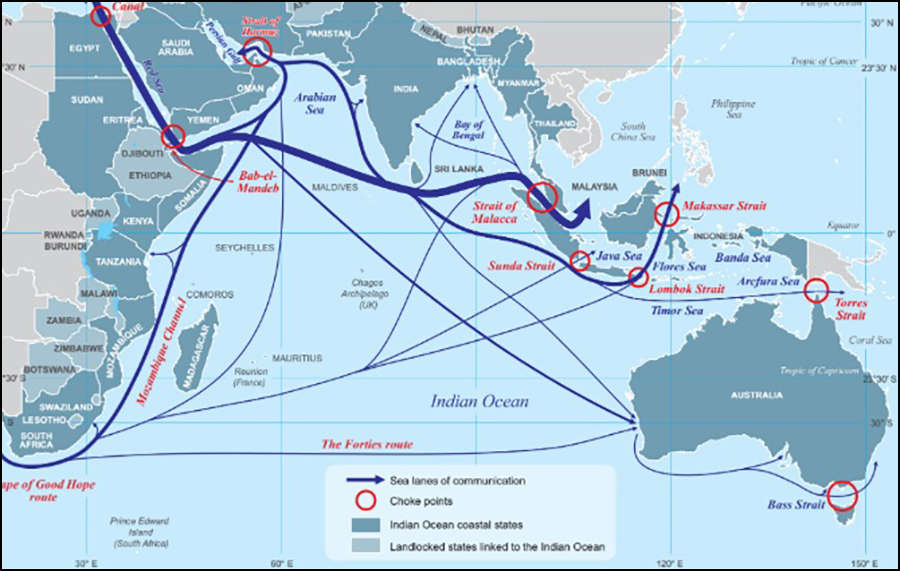

India has since been working towards establishing its dominance in the IOR keeping Sri Lanka as its focal point. Highlighting the geo-political importance of Sri Lanka, Dr. Samatha Mallempati wrote, “Since the region accounts for fifty percent of world maritime trade and seventy percent of global trade in oil and gas, there is a greater need to safeguard the sea lanes of communication. The increasing strategic significance of island states in the region therefore assumed importance. The island states such as Sri Lanka is looking to play a much bigger role by leveraging their geographical location.”

The perception in New Delhi that Sri Lanka is leveraging its geographical location to define geo-politics in the IOR, was what paved for the MoU on defence co-operation India signed with Sri Lanka, that for 05 years would provide India adequate space to influence Sri Lankan geo-politics in its favour. But the fact is, all these agreements and treaties are about IOR peace and stability and the influence “foreign countries” may have in it. The Sri Lankan moratorium was also about research ships of foreign countries, docking in our ports.

How would the UN flagged marine research ship “Dr. Fridtjof Nansen” interfere in IOR stability and peace? The request to FAO for marine research in our waters had gone from the SL Government, never mind who led the government. FAO is focussed on sustainable fisheries management and this modern, fully equipped ship for marine research is used mainly in African and Indian Ocean waters in collaboration with NORAD to support developing countries with research based fisheries management. That perhaps was the only reason for the previous government to request the FAO to visit Sri Lankan waters. Mind you, that request for FAO to undertake marine research in our waters, went out while the moratorium on foreign research ships was fully effective.

Whatever the bureaucracy at the FM says, a seasoned politician like Vijitha Herath who had been in parliament for 25 years to date from year 2000, should know the difference between this UN flagged marine research ship and other research ships owned by individual countries. Anything flagged as “UN” is common property of 195 sovereign nation States who are UN members. This ignorance therefore very clearly exhibits the JVP/NPP leadership as the most intellectually timid leadership to have been voted to power since 1948 independence.

Kusal Perera

20 June, 2025

Passengers jump from plane’s wing after fire alert on Spain flight, triggers panic

CBSL extends Perpetual Treasuries suspension for six months